Great Pots from the Traditions of North & South Carolina: Exhibition at the Pottery Center in Seagrove, North Carolina.

Over the past year, Mark has been busier than usual. As well as making his usual quota of pots, he's been helping to organise the International Woodfire Conference (which happened a few weeks ago) and the Great Pots exhibition that coincided with it. During the winter, after we 'd fired the salt kiln, Mark drove around the South meeting collectors and pickers and dealers, trying to find the very best examples of traditional North and South Carolinian pottery. The idea was to showcase the rich history of pot making in this area to all of the world-class woodfire potters who would be visiting for the conference.

The proceedings opened at the Pottery Center, with the Great Pots on display. We ate NC barbeque, (pulled pork, collards, hush puppies, and the like), chatted with new and old friends and took in the pots, excited for the weekend's events to come.

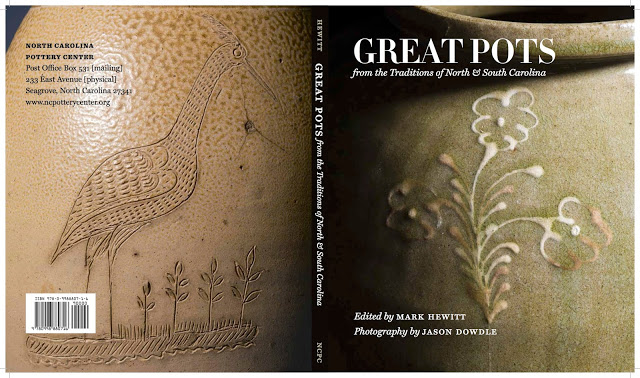

This exhibition and accompanying book (above; it can be purchased here) acts as a sequel to Mark's previous exhibition and book, The Potter's Eye. A few of the same pots were included, such the one from the cover of The Potter's Eye by Solomon Loy. It was a real treat to see this one up close! When I asked why he wanted a few of these previous pots, he simply said, "I just had to show those ones"... they acted as a starting point -- a measure of quality. The choice of pots was mostly a matter of which ones Mark particularly liked and felt needed to be shown.

This makes the exhibition all the interesting because his perspective is different from the usual art curator or collector. Being a potter, he appreciates all aspects of the pots, from the forms, to the decorations, to the way the handles were put on, to the firing, to the clay etc etc. In this way, the exhibition and accompanying book are truly a sequel to The Potter's Eye.

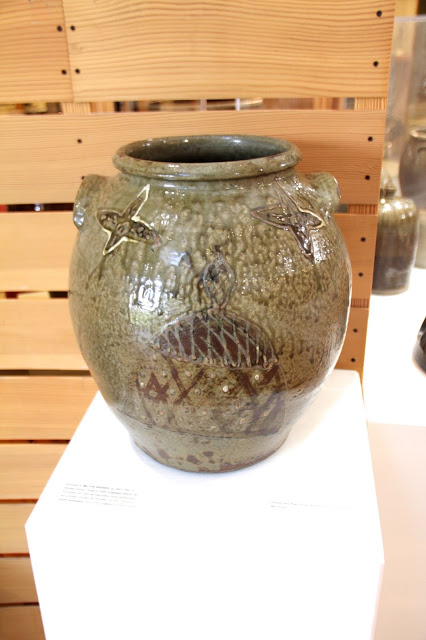

There are over 150 pots in the exhibition and book, each with a little lyrical note from Mark portending to why he included that particular pot. The pots are organised into five sections, with informative, engaging essays from authorities on them: Linda Carnes-McNaughton on earthenware and the pots from Alamance County, NC, Charles (Terry) Zug on alkaline and salt-glazed wares, Philip Wingard on South Carolina stoneware. As there were so many pots to fit into the Pottery center, Mark was creative in his display; arranging groups of pots together, almost in still life scenes. This was partly out of necessity but also inspired by an exhibition of ceramics called "Parades," organised by Gwyn Hanssen Pigott (2006-2008), at the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington DC.

I went back and revisited the exhibition last weekend with less people around and was amazed by the quality and breadth of the work. It was wonderful to be able to walk around them slowly, feeling the surfaces and examining the clay bodies. The pots have a power in person; particularly the larger jars, churns, and jugs. I love the wide bellies, high shoulders, and strong forms of many of these pots. The wide range of wood-fired surfaces struck me too; all different permutations of wood ash deposits, salt and alkaline glazes, over and under fired, as well as dainty pinkish deer spots. I particularly enjoyed the accidental surfaces from firings gone awry; you can see some pots where the kiln bricks melted glassy drips onto them. But also, in contrast to these gnarlier examples, I loved seeing the crisp, delightful incising of Chester Webster's work.

To start this post, I have included a few pictures of the exhibition as it was laid out in the Pottery Center. These quick snaps don't really do the pots justice, but give a sense of the exhibition. Below those are some of the pictures used in the book (which Mark kindly sent me), taken by professional craft photographer Jason Dowdle.

The exhibition is up until July 22nd, 2017, so get over to Seagrove and check it out if you can! If not, there's always the book. It is a very nicely put-together tome with excellent photographs, as you should get a taste of in this post.

Now on to Jason Dowdle's professional pictures. I've included the entries as they are in the book: with all the details of the pots and Mark's comments underneath. Enjoy!

Alkaline Glazed Stoneware (NC)

Alamance County (NC) Salt Glaze

Earthenware from North Carolina

The proceedings opened at the Pottery Center, with the Great Pots on display. We ate NC barbeque, (pulled pork, collards, hush puppies, and the like), chatted with new and old friends and took in the pots, excited for the weekend's events to come.

This exhibition and accompanying book (above; it can be purchased here) acts as a sequel to Mark's previous exhibition and book, The Potter's Eye. A few of the same pots were included, such the one from the cover of The Potter's Eye by Solomon Loy. It was a real treat to see this one up close! When I asked why he wanted a few of these previous pots, he simply said, "I just had to show those ones"... they acted as a starting point -- a measure of quality. The choice of pots was mostly a matter of which ones Mark particularly liked and felt needed to be shown.

This makes the exhibition all the interesting because his perspective is different from the usual art curator or collector. Being a potter, he appreciates all aspects of the pots, from the forms, to the decorations, to the way the handles were put on, to the firing, to the clay etc etc. In this way, the exhibition and accompanying book are truly a sequel to The Potter's Eye.

There are over 150 pots in the exhibition and book, each with a little lyrical note from Mark portending to why he included that particular pot. The pots are organised into five sections, with informative, engaging essays from authorities on them: Linda Carnes-McNaughton on earthenware and the pots from Alamance County, NC, Charles (Terry) Zug on alkaline and salt-glazed wares, Philip Wingard on South Carolina stoneware. As there were so many pots to fit into the Pottery center, Mark was creative in his display; arranging groups of pots together, almost in still life scenes. This was partly out of necessity but also inspired by an exhibition of ceramics called "Parades," organised by Gwyn Hanssen Pigott (2006-2008), at the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington DC.

I went back and revisited the exhibition last weekend with less people around and was amazed by the quality and breadth of the work. It was wonderful to be able to walk around them slowly, feeling the surfaces and examining the clay bodies. The pots have a power in person; particularly the larger jars, churns, and jugs. I love the wide bellies, high shoulders, and strong forms of many of these pots. The wide range of wood-fired surfaces struck me too; all different permutations of wood ash deposits, salt and alkaline glazes, over and under fired, as well as dainty pinkish deer spots. I particularly enjoyed the accidental surfaces from firings gone awry; you can see some pots where the kiln bricks melted glassy drips onto them. But also, in contrast to these gnarlier examples, I loved seeing the crisp, delightful incising of Chester Webster's work.

To start this post, I have included a few pictures of the exhibition as it was laid out in the Pottery Center. These quick snaps don't really do the pots justice, but give a sense of the exhibition. Below those are some of the pictures used in the book (which Mark kindly sent me), taken by professional craft photographer Jason Dowdle.

The exhibition is up until July 22nd, 2017, so get over to Seagrove and check it out if you can! If not, there's always the book. It is a very nicely put-together tome with excellent photographs, as you should get a taste of in this post.

I love these earthenware pots, particularly the sugar bowl up front. It is so alive and expressive, over the top in its slip-trailed decoration but humble in form.

This large mixing bowl is amazing. The glaze must have been applied really thickly as it ran down and puddled in one side of the base.

This pot is attributed to Milton Rhodes (1843-52). I find the decoration very odd. You can see it two ways; either a slip trailed woman in a hooped skirt is at the center, with flowers up above, or the flowers are eyes, her torso is a nose and her skirt is a gaping mouth. Great shape, but I find the decoration rather unsettling!

|

| Mr. Hewitt giving a talk about how the exhibition came to fruition, in the teaching wing of the Pottery Center. |

One gallon crock stamped JD CRAVEN BROWER'S MILL, N.C. I rather fancy this one as a bread bin.

Jugs!

I like how slender this whisky jug is. Pretty light too (not that I picked it up or anything).

I really like this Chester Webster jug too: despite being underfired, it has a lot going on in the surface. I like shape of the the neck and lip too.

Alkaline Glazed Stoneware (NC)

DANIEL SEAGLE, ca 1805–1867, Lincoln County, NC. Fifteen-gallon jar. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. 18 × 19 in. Collection of Quincy, Betty & Samuel Scarborough.

Orthodox, generous, and calm, with somber notes, Daniel Seagle’s giant pot possesses an accuracy and girth that set a standard.

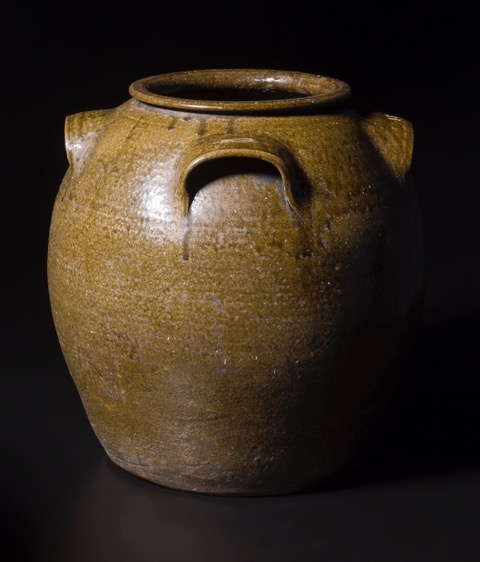

DANIEL SEAGLE, ca 1805–1867, Lincoln County, NC. Five-gallon jar. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. 16 × 13 in. Collection of Danny Richard.

Pottery collector Danny Richard got a call from someone in Lincoln County saying they’d found old pots buried under their house. They knew he was interested. Covered in dirt, a pig in a poke, he paid the price. All except one looked cracked or broken. He put them in his pickup, drove away, then stopped by a creek, took them to the water, and used his shirt to wash away the dirt. This one was baptized intact.

JAMES FRANKLIN SEAGLE, 1829–1892, Lincoln County, NC. Half-gallon jug. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. 9½ × 6 in. Collection of Scott & Wendy Smith.

Another talented Seagle, Daniel’s son James Franklin, precise, disciplined, carrying on where his father left off. Different times though, the pre– and post–Civil War South.

ISAAC LEFEVERS, 1831–1864, Lincoln County, NC. Five-gallon jug. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. 18 × 13 in. Collection of Quincy, Betty & Samuel Scarborough.

IL: tragically rare letters. The orphaned apprentice who died at thirty-three. The stick figure–like drips, from excess glaze tipped back after the pot was dunked, are deliberate. If you pay attention, control of process generates ornament.

SYLVANUS HARTSOE, 1850–1926, Lincoln County, NC. Large rundlet with glass melt. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. 13 × 18 in. Collection of Allan & Barry Huffman.

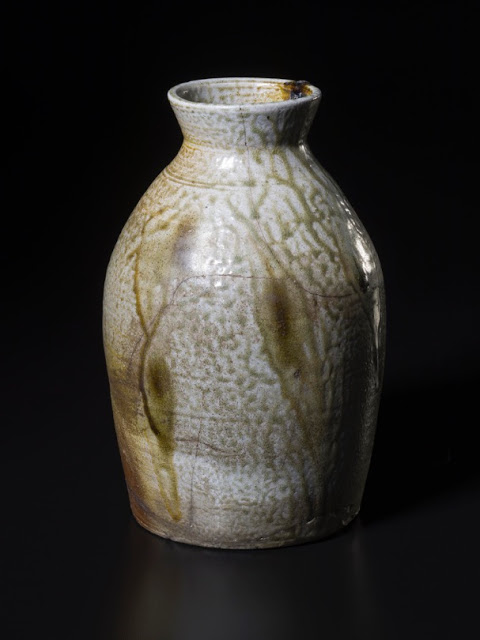

A submarine or a “medicine” bottle? Glaze application drips and a pool of glass give a liquid air to this curious container.

UNKNOWN MAKER, Lincoln County, NC. Five-gallon jar with glass runs, ca 1875. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. 16¼ × 13 in. Collection of Scott & Wendy Smith.

Moore and Randolph County (NC) Salt Glaze

CHESTER WEBSTER, 1801–1882, Fayetteville, NC. One-gallon jug, underfired with pale wad marks. Salt-glazed stoneware. 6 × 10 in. Collection of Quincy, Betty & Samuel Scarborough.

Discarded, damaged, and unearthed at the shard heap, it is an exquisite reject. The frost nipped it, it never grew up, it fell before its time. Contemporary in its ethereal wad markings, it held promise, but never water.

CHESTER WEBSTER, 1799-1882, Randolph County, NC. Three-gallon jar with incised bird, fish, and date, 1851. Salt-glazed stoneware. 15 × 12 in. Collection of Tommy & Ann Cranford.

A whimsical bird plucks a fly from the date-filled air, while a fish pirouettes behind. Chester’s humor didn’t fester.

CHESTER WEBSTER, 1799–1882, Randolph County, NC. Two-gallon jug, with incised bird. Salt-glazed stoneware. 15 × 9 in. Collection of Quincy, Betty & Samuel Scarborough.

A perfectly poised profile rewarded with a trilling bird, or is it catching flies? Either way it’s smiling.

CHESTER WEBSTER, 1799–1882, Randolph County, NC. Four-gallon jug, with incised heron. 18 × 10 in. Collection of Tommy & Ann Cranford.

Webster incised herons, Cardew painted them. One flew overhead when I first stood where my chimney would be.

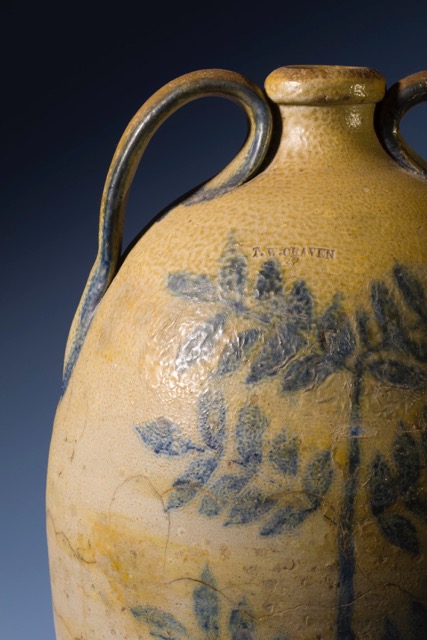

T. W. CRAVEN, 1829–1858, Randolph County, NC. Ten-gallon double-handled jug, with cobalt sumac tree. Salt-glazed stoneware. 21 × 14 in. Collection of Quincy, Betty & Samuel Scarborough.

Bewitched, bothered, and bewildered, this captivating beauty was damaged, perhaps by frost, and crudely repaired with epoxy. There’s no hiding loveliness, though.

NICHOLAS FOX, 1797–1858, Chatham County, NC. Half-gallon jug, with kiln drips. Salt-glazed stoneware. 7 × 6 in. Collection of William Ivey.

A sweet shape with juicy drips and luscious ash.

J. J. OWEN, 1830–1905, Moore County, NC. Two-gallon patent jar. Salt-glazed stoneware. 17 × 10 in. Collection of Jugtown Pottery.

Beaten, broken, maybe even shot, this jar is an invalid. Dignified nonetheless by its spectacular tonal variation, its hole is a badge of honor for years of service.

J. H. OWEN, 1866–1923, Moore County, NC. Drain tile. Salt-glazed stoneware. 15 × 7 in. Collection of Jugtown Pottery.

A piece of minimalist abstract art? It depends on the context.

TEAGUE FAMILY, Randolph County, NC. Grave Marker for James R. Teague, 1938. Salt-glazed stoneware. Gift of Charles G. Zug III, Ackland Art Museum, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 84.42.1. (Photographs by Scott Richard Hankins).

This one gives me the shivers.

Alamance County (NC) Salt Glaze

SOLOMON LOY, 1805–ca 1860, Alamance County, NC. One-and-a-half-gallon pitcher with ash runs and kiln drips. Salt-glazed stoneware. 11½ × 9 in. Collection of Robert & Jimmi Hodgin.

Its shape is stiff and squat, but its delicately pinched throat and spout combine with the glistening ash runs and a diaphanous kiln drip to make it spectacular.

SOLOMON LOY, 1805–ca 1860, Alamance County, NC. One-gallon jug with ash runs and kiln drips. Salt-glazed stoneware. 11 × 7 in. Collection of Robert & Jimmi Hodgin.

Add more colors to the mix, and here’s another wonder. Dark patches from salt shadows and a swath of slow-cooled ash distinguish this treasure.

GROUP OF CANNING JARS

Sleek, narrow-mouthed, and infinitely varied, these stunning canning jars are unique to Alamance County. Like leaves they shimmer and glow, all dappled and drippy, set up for a show.

TIMOTHY BOGGS, 1849–ca 1910, Alamance County, NC. Canning jar. Salt-glazed stoneware. 11 × 7½ in. Collection of Robert & Jimmi Hodgin.

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall, but didn’t quite break. Injured but not discarded, no longer useful but valuable nonetheless. An exotic, wild, damaged beauty, treasured despite its flaws, for its flaws.

SOLOMON LOY, 1805–ca 1860, Alamance County, NC. Eight-gallon jar. Salt-glazed stoneware. 20 × 12 in. Collection of Joseph & Amanda Sand.

Of all the potters in the South, Solomon Loy seems to have deliberately composed the abstract appearance of his stoneware pots, artfully finessing the process of salt firing, with its accompanying kiln drips and ash runs, and consciously layering seductive colors and enigmatic textures.

SOLOMON LOY, 1805–ca 1860, Alamance County, NC. Ten-gallon jar with ash runs and kiln drips, stamped “S. LOY 1856 10.” Salt-glazed stoneware. 19 × 14 in. Collection of Robert & Jimmi Hodgin.

An amputee, with stumps where its handles used to be, this big jar remains magnificent, proud, and undaunted.

Earthenware from North Carolina

JACOB WEAVER II, 1774–1846, Catawba County, NC. Plate, ca 1790. Lead-glazed earthenware. 4 × 9 1/2 in. Collection of Tommy & Ann Cranford.

Unlike most of the early earthenware potters in North Carolina, who worked in the eastern Piedmont, Jacob Weaver built his kiln in Catawba County, known primarily for its later alkaline-glaze tradition. This kiln site and plate were only recently discovered. Simple, controlled, and lively, the plate has a beautifully executed set of polychrome slip-trailed lines with sgraffitoed rim decoration. Incredibly, it has remained in perfect condition since the 1790s.

SOLOMON LOY, 1805– ca 1860, St. Asaph’s tradition, Alamance County, NC. Small plate, ca 1820–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. 2 × 6½ in. Collection of Robert & Jimmi Hodgin.

Fleshy pink blotches with black and white dots. A straightforward description says little about the wonders of this masterpiece. Warm and embraceable, with a cloudy gray quadrant where the smoke choked the gritty clay into soft, blushing halos. Dots float along the surface like confetti.

Attributed to WILLIAM DENNIS New Salem Quakers, Randolph County, NC. Plate, ca 1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. 2¼ × 10¾ in. Collection of Stephen C. Compton.

An autumnal mood resides in the fernlike decoration and deciduously swaging border of this plate. Its character marks the reliability of the cyclical rhythm of the seasons.

SOLOMON LOY, 1805–ca 1860, St. Asaph’s tradition, Alamance County, NC. Miniature mug, ca 1820–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. 2½ × 3½ in. Collection of Tommy & Ann Cranford.

One can only imagine the delight a youngster would have using this sweet spattered mug, or entertaining with it as part of a doll’s tea set. Childs play, imaginative and unbroken.

Pots from South Carolina

THOMAS CHANDLER, 1810–1854, Thomas Chandler Stoneware Factory, Kirksey’s Crossroads, Edgefield District, SC.Double-handled five-gallon jug with slip-trailed floral motif, stamped “CHANDLER MAKER,” ca 1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. 19 × 11 in. Collection of David Ward.

Soft color on strong form while the decoration sits perfectly on the shoulder. Big blue celadon, calm and authoritative.

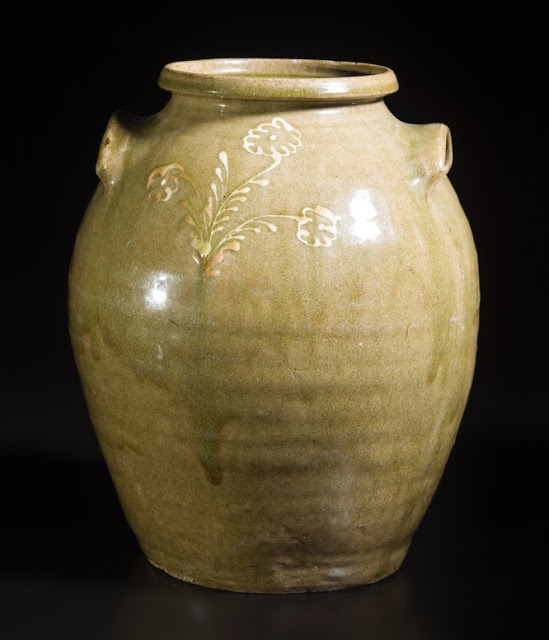

THOMAS CHANDLER, 1810–1854, C. Rhodes Factory, Shaw’s Creek, Edgefield District, SC. Three-gallon jar with slip-trailed floral motif, ca 1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. 15 × 11 in. Collection of Jim Witkowski.

The shape is superb, the handles snug, and flowers flow — alive, deftly drawn. A different performance on each side, all bathed in luxuriant celadon, the perfect tone. Layer upon layer of slightly changing excellence, Chandler’s repeated themes and variations resemble a fugue.

UNKNOWN MAKER, C. Rhodes Factory, Shaw’s Creek, Edgefield District, SC. Five-gallon Jar, slip-decorated with a “number flower” on one side and a flower on the other, ca 1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware (with repaired neck). 14½ × 12 in. Collection of John LaFoy.

Does a repair ruin a pot? Is such a flaw acceptable in an exhibition? The rest of the pot is fabulous, the “5” flower (the rare Rhodesian genus flora numerica), with a second exotic on its rear. But that green neck? Probably done with great care in the 1960s by someone who should have known better, it’s like a blemish on a pretty forehead.

UNKNOWN MAKER, C. Rhodes Factory, Shaw’s Creek, Edgefield District, SC. Three-gallon jar, slip-decorated with the profile of a man on one side and a flower on the other, ca 1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. 14½ × 12 in. Collection of John LaFoy.

The slip was dark, the figure’s race unclear. A person in profile with hair, an eye, an ear, teeth, a kerchief, buttons, frills, and fingers, warm ochre red bleeding through the glaze. A complex moment recorded. A life.

UNKNOWN MAKER, Upstate South Carolina, or Thomas Chandler School, Martintown Road Pottery, Kirksey’s Crossroads, Edgefield District, SC, or John D. Leopard, Bacon Level, Randolph County, Alabama. Ten-gallon double-handled jug, with red ochre bleeds and residual ochre nuggets. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. 20 × 14 in. Collection of David Ward.

UNKNOWN MAKER, Upstate South Carolina, or Thomas Chandler School, Martintown Road Pottery, Kirksey’s Crossroads, Edgefield District, SC, or John D. Leopard, Bacon Level, Randolph County, Alabama. Ten-gallon double-handled jug, with red ochre bleeds and residual ochre nuggets. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. 20 × 14 in. Collection of David Ward.

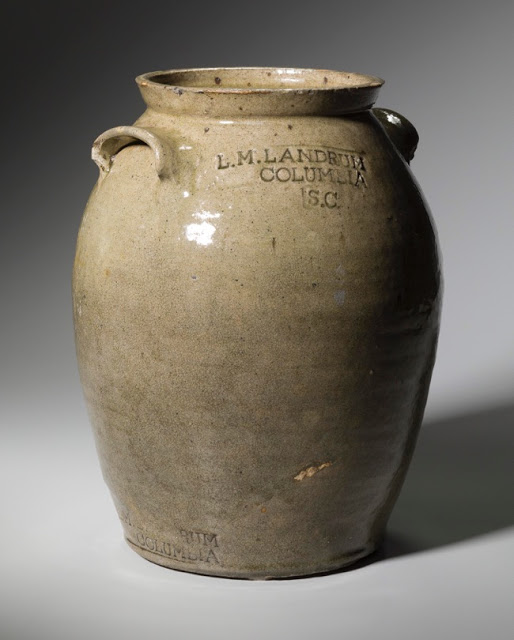

LINNAEUS LANDRUM, ca 1829–1891, Landrum Pottery, Eight Mile Branch, Columbia, SC. Three-gallon jar with feldspar glaze, stamped twice “L.M. Landrum, Columbia S.C.,” ca 1860. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. 15½ × 11½ in. Study collection of Philip & Deborah Wingard.

Maybe it’s the crazing, the color, the shape, or the feeling it conveys? Somehow the gray-green, silky soft patina and sweet shape make this one an absolute winner.

DAVID DRAKE, ca 1800–1870, Lewis Miles Pottery, Horse Creek, Edgefield, SC. Twenty-gallon jar inscribed, “Nineteen days before Chrismas Eve — Lots of people after its over, how they will greave . . . LM, Dave, Dec 6 1858.” Alkaline-glazed stoneware. 21 × 19½ in. Collection of Corbett Neal Toussaint.

Dave Drake’s verse haunts, as do others on his pots. Some of them express resistance in the slave South. This one, for instance, may refer to the grim practice of giving slaves to a new owner as a Christmas present, or of leasing enslaved laborers to other area slaveholders for one-year stints, starting on New Year’s Day. Good tidings on Christ’s birthday? Joy, peace, love… and families torn apart? The enslaved potter Dave Drake exposes their grief and suffering through his hands, intellect, and voice. Drake was taught to read and write---a star that was allowed to shine, while others were not.

Let there be light!