I was worried that this firing was not going to yield any successful results because I accidentally over-fired the kiln.

Cone 10 was just starting to melt, so I adjusted the settings (opened the damper a bit) and walked away, thinking it would probably be done in a half hour or so. Normally I set an alarm on my phone to remind me to check back, but this time I did not. Then I became engrossed in making pots and forgot all about the kiln.

I remembered about an hour and a half later. Ran over to the kiln. Found the pyro reading 2357 (way hot). Didn’t even check the cones, I knew it was too hot. Turned the gas and air off as quickly as possible. With a sigh, I pulled out the peephole to check the cones. My regular cone packs read 011, 3, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11. Cone 11 is normally my safety cone. I try to fire cone 10 down and cone 11 just strating. Well, there was no evidence of any cones left standing. Cone 11 was down. Like way down. Flat. So I figure it was probably cone 12 in there.

Exhibit a:

I walked away cursing myself. Mindfulness!!!! I had a lot of tests in the kiln, and was really hoping for some answers, especially with the jun glazes.

Anyway, when I opened the kiln, I found it was actually pretty good. I was shocked. Not many of the glaze tests ran. I have been working toward more stable jun and tenmoku glazes so this was actually a really good test. Especially for firing them in a wood kiln with all that extra flux.

Sometimes mistakes work out! In the cups you see here, I tested various methods of applying copper carbonate to the jun glaze. I love the old Song Dynasty pots that have swathes of purple on them.

These photographs aren’t the best, but overall, the best results were from copper carbonate sprayed on the outer surface of a thick jun glaze.

I basically just mixed the copper carbonate with a small amount of bentonite and water until it was a glaze-like consistency before applying. I noticed that it was way easier to overdo it with a brush than spraying. If you get too much copper on there, it turns the area green.

I accidentally dropped one of the cups that had this copper carbonate mix poured on the outside of the jun glaze. Another happy accident! It showed me quite a bit about the effect. Here are the sherds…

It looks so bright under the layer of glaze. I wonder if this is from being more reduced. I am considering trying a firing with some late heavy reduction. This firing was more of as neutral atmosphere towards the end.

Other interesting finding… The bowls that I have fired twice already came out brilliantly this time:

These results are much bluer than previously. I would say from this that refiring these jun glazes can really improve them.

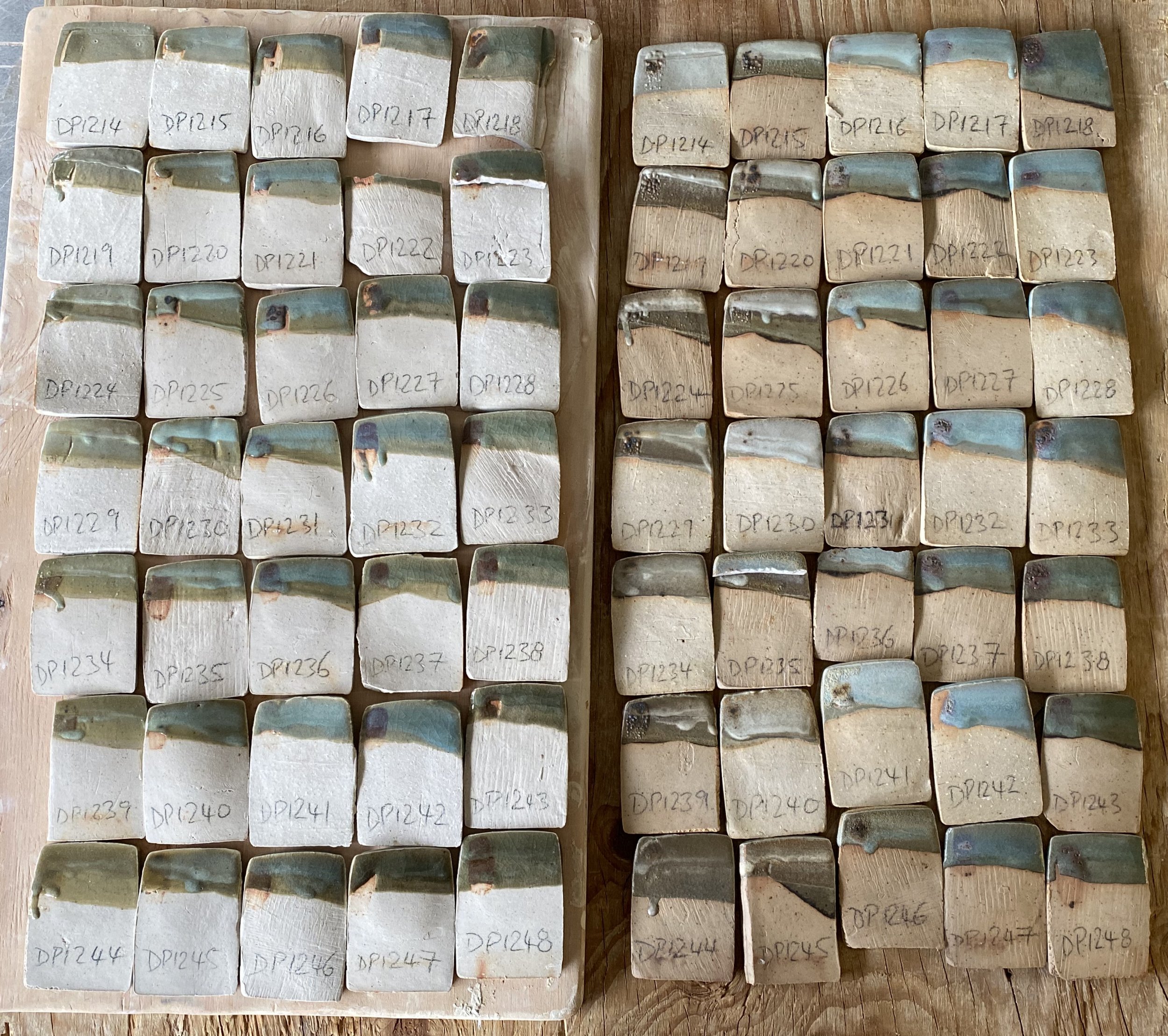

Here are some more test tiles…

I have decided to mix a large batch of DP1264. The composition is as follows:

50% Devil’s a playground granite, 20% Wollastonite, 20% silica, 10% mahavir feldspar, + 2% bentonite, 2% bone ash, 1.5% red iron oxide and 1.5% Dolomite.

DP1264 seems to work. It is a solid glaze that doesn’t run, appears opalescent if reduced well and does not require a special cooling cycle. I think that the greenish cast is more to do with the firing than the composition, but I may be wrong. I could try to lower the silica and raise the mahavir potash feldspar a little as this seems to produce bluer results (but less reliably opalescent). Perhaps something like 18% of each silica and wollastonite with 14% mahavir might be a touch bluer. I shall try this!

Here’s DP1264 on a bowl…

Other promising results:

Jun over tenmokus. DP1302 is DP1264 over DP …… and DP1303 is DP1264 over ……….

They both worked, but to my eye, the effect is nicer in DP1302. I will definitely be trying this on some teabowls.